Plural Public Law: Relevance and Influence

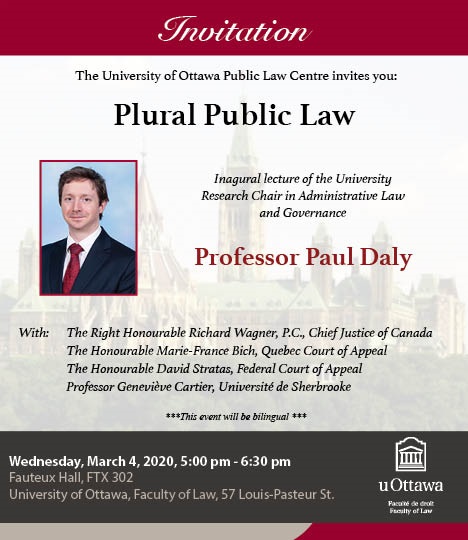

I gave my inaugural lecture as the University Research Chair in Administrative Law at the University of Ottawa last month. You can watch the lecture here (after some introductory remarks from Dean Sylvestre, Chief Justice Wagner and Justice Bich). The comments from my respondents, Justice Stratas and Professor Cartier can be found here. This is the fifth and final post in a series: the first, second, third and fourth installments can be accessed here, here, here and here.

And so I turn, lastly, to relevance and influence. Much of our work — perhaps all of it — assumes that public lawyers ought to be relevant and influential. Otherwise we would not be writing and teaching but twiddling our thumbs in our offices, practicing law or simply watching time go by.

Why do we think others — our students, fellow academics, practitioners of law and members of the wider community — should listen to us, when we stand at our lecterns or sit at our keyboards? For one thing, public lawyers are concerned with the effective functioning of the institutions of government which touch ordinary people’s lives in all sorts of ways, every day. Academic concern for doctrinal rigour and coherence is, therefore, valuable — ultimately, though perhaps we are so modest that we would prefer to say it sotto voce, we want to make government work for the people it serves. Even intra-academic debates on potentially picayune points of disagreement have this (or something closely related to this) as their ultimate goal.

Beyond that, the principles we develop and derive are normatively attractive. They are good principles. Adherence to the rule of law and citizen participation, to good administration, to democracy and electoral mandates, to federalism and to separation of powers, makes for a better world. On the detailed application of these principles in different contexts reasonable minds might of course differ. But at the very least, I think it is a good thing that these principles are part of public discussion and political debate.

And this discussion and debate will be hugely important in the coming years. The 2020s will be marked by: designing algorithms, content moderation standards, internal review mechanisms and oversight functions for social media platforms; by developing transnational regulatory structures to manage climate change, economic contagion, mass migration and pandemics; and by integrating advanced forms of information technology, such as machine learning, into public administration.

What has plural public law, specifically, to do with public lawyers being relevant and influential in the modern world? Being relevant and influential in our fast-moving times is a challenge but one which is much easier to surmount with a principled framework to hand. Where there is a torrent of information pouring forth from a plurality of sources, a principled framework helps to manage the flow. The American Law Institute’s Restatements emerged in the early-20th century to manage an earlier increase in the volume of raw material to deal with.[1] Perhaps I cannot read the 17,000 decisions in which Dunsmuir has been cited. If I have a principled framework, drawn from a plurality of sources, inspired by a plurality of methodologies – a living tree, as it were, changing over time – the task of making sense of the volume of material is made much easier. Relevance to discussion and debate is much more attainable.

So, too, is influence. Public lawyers armed with principles – like the rule of law and good administration – derived from a plurality of sources and honed by constant exposure to a plurality of methodologies, arrive better equipped for debate and discussion on the important issues of the day: whether Facebook’s new Oversight Board has sufficient independence to play a meaningful role in the review of controversial decisions about what may or may not be posted on the company’s massive platform; whether our transnational structures for managing the movement of capital and people and responding to the problem of climate change adequately balance the need for robust controls with the economic interests of individuals and of future generations; and whether it is appropriate to use machine learning to distribute benefits to and revoke privileges from the citizenry. With principles in hand, public lawyers can make incisive contributions to political debate and public discussion on these important issues and more, being not just relevant but influential and contributing to a better world.

[1] See generally G Edward White, “The American Law Institute and the Triumph of Modernist Jurisprudence” (1987) 15 Law & History Review 1.

This content has been updated on April 2, 2020 at 14:31.